Energy Security Intelligence Research

ESIR

ESG STRATEGY RISK and COMPLIANCE PLANNING AGENDA 2050

CANADA

Is Canadian Oil Bottoming out?

- New risks for Canadian's oil sands in Alberta

- Royalties and Climate Change Policy

- Strategies for export routes; and

- Western Canadian export capacity Vs Supply

Understanding Doing Business in Canada's Oil and Gas Sectors-Managing Political and Economic Risk

As everybody in the oil industry knows, it’s battling against low crude prices, tougher regulations, alternative forms of fuel and power, and rising upstream costs. From China to Libya, operators in many of the major oil-producing nations are struggling to achieve breakeven costs of production and most analysts believe things will get worse before they get better.

Therefore, many operators are sweating every dollar of value from their physical infrastructure just to break even on the cost of production. But there’s only so much value which can be wrung out of physical assets and the smartest operators are turning to a new kind of infrastructure to face today’s and tomorrow’s challenges. It’s called data infrastructure. And it’s this technology which relays vital information from great depths, provides 24/7 monitoring of the condition of mission-critical equipment, monitors for safety issues and much else.

But important as this information is, operators are drowning in fragmented, critical, time-series data pouring out of multiple and diverse systems that don’t talk to each other. The burning imperative now is how to harness all this vital information and convert it to data you can use.

Therefore, understanding doing business in Canadian oil and gas sector outline the business environment, economic and political reforms, technological innovations, regulatory and legal structures in place that investors should take into consideration before entering new market in the energy sector in Canada. Investing in data collection for predictive operation; and the VAPOR approach in page 27 & 33 system provides a platform that converts an ever-mounting deluge of data into a coherent whole that allows operators to save money, meet regulatory requirements and improve safety. Some E&P users of the VAPOR System have cut barrels of oil equivalent per day (boe/d) costs by up to 2-5% while others have cut their controllable margin in logistics by 1-5%. For example, in the hard-hit Alberta, some operators have halved average unit operating costs in the last two years, from $29.70 per barrel ($/b) to $15.30/b. This consulting and advisory includes the following:

- Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………………………2

- Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………….5

- Overview of Canada’s Oil and Gas Sectors…………………………………………………6

- Climate and Environmental Challenges…………………………………………………….11

- New Risks for Canadian Oil Sands in Alberta…………………………………………….14

- Royalties and Tax System………………………………………………………………………….17

- Local Employment, Procurement and Training………………………………………… 19

- Export Routes Visibility Study…………………………………………………………………….20

- Is Canadian Oil Bottoming out?.......................................................................21

- Understanding the Race for Lower Costs……………………………………………………23

- Investing in Data Collection for Predictive Operations………………………………26

- Obtaining Energy Sector Insurance for Oil and Gas Operations………………….31

- Applying the analytical approach-VAPOR……………………………………………………33

- Negotiating and Evaluating Fiscal Regimes for Resource Projects in Canada…36

- Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………………………….39

- References…………………………………………………………………………………………………….41

Canada Oily heartland, Edmonton, Alberta's capital expected to produce 3.8 million barrels of oil (b/d) by 2022, that will double 2015 production from the oil sands, and will trickle down to refineries in the US, China and beyond. Although, the Canadian oil-sands industry is still in its infancy, since 1967, the country has produced about 8.8 million cumulative oil-sands barrels, according to the Alberta's Energy Resources Conservation Board (ERCB). A figure that will reach 1.39 billion barrel-a-year within the decade. Even at those rates, barely 1% of the resources has been produced.

Not all oil sands are the same, however, different methods are used to wring the bitumen from the ground. Trucks and shovels account for almost half of production now. But more than 80% of the resources will be recovered in situ using horizontal wells connected to pipelines.

Moreover, the Canadian government estimates C$560 billion of investment will be needed to develop the country's energy resources, including oil sands, which has been formally deemed a vital strategic asset. The new policy is meant to strike a balance between attracting much-needed foreign investment while assuaging domestic concerns over Asian state-owned companies' increasing prominence in the energy sector.

Under Canadian law takeovers of domestic firms where the transaction is valued at more than C$330 million must be deemed to be a net benefit of the country. But if the new law were meant to further define what constitutes a "net benefit", then the policy regarding state-owned companies raises more questions than it answers.

However, Canada's dependence on petroleum exports means its economy has fared worse than most of its G7 peers since oil started tumbling in mid-2014. For example, in 2013 oil accounted for a tenth of its GDP and a third of its exports, or roughly C$129bn ($88.4bn) per year of its C$1.8 trillion economy. Therefore, oil's fall threatens Canada's once leading economic performance. Layoffs in the energy-concentrating in Alberta-have already topped 100,000, with more than 20,000 administrative positions axed in Calgary alone.

Canada's dearth to deluge

It is a prospect that seemed unthinkable for oil sands producers just a few months ago: Canada, which faced a dire shortage of space on its ageing transportation network, might now be over-piped. Two major pipeline expansions have been approved, a third is moving through the regulatory process; throw in a revived Keystone XL (KXL), and suddenly producers may get 2m b/d of new capacity flowing east, west and south.

It started in late November when prime minister Justin Trudeau gave the green light for KinderMorgan's controversial C$6.8bn ($5.2bn) TransMountain expansion (TMX) line, while turfing Enbridge's Northern Gateway proposal at the same time.

TMX will triple to 0.9m b/d the capacity on an existing line linking Alberta's oil sands to Vancouver on the west, providing a much-needed outlet to Asia. Despite protests and fierce opposition, the British Columbia government surrendered necessary environmental certificates shortly after the approval, all but ensuring it will be built. Though it still faces court challenges, construction is likely to start this autumn with the first oil flowing through the pipeline by 2018.

Less controversial was Trudeau's approval of Enbridge's C$7bn Line 3 expansion south into the US. This will replace a link into the company's US Lakehead system that ruptured in 2010, fouling the Kalamazoo River in Michigan. As part of a settlement with the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the company has reduced the pipeline's operating pressure—which effectively cut capacity in half to around 380,000 b/d. Facing a choice from the EPA either to replace the pipeline or pull it out of the ground, it has chosen to replace and expand Line 3. The new investment will restore capacity to its original 0.76m b/d and allow for further expansion to 0.915m b/d.

US president Donald Trump's 24 January executive order aimed at restarting the stalled KXL project could end up adding another 0.83m b/d of capacity. Little surprise, project backer TransCanada refiled its application almost immediately after the ink was dry on Trump's decree, and the Canadian firm is already thinking of expanding KXL to more than 1.1m b/d. The decision now goes to Trump's new Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, who has until late March to act. There is little doubt which side the former oilman will come down on.

Add in more than 100,000 b/d of oil shipped by rail—a number only growing with new investment from producers Imperial Oil, Cenovus and others—and Canadian producers are facing a whole different, but not unwelcome, dilemma: where to send production that is expected to top 6.1m b/d by 2040, according to International Energy Agency forecasts.

Canada sends more than 98% of its oil exports to the US, which has resulted in steep discounts for its expensive barrels. In glutted times—when producers are competing to send oil down the pipeline—the discount can be 50% of global benchmarks.

The rationale for new pipes is obvious from an economic point of view. Presently two-thirds of Canadian barrels go to a handful of refineries in the US Midwest, effectively overloading the market and worsening price differentials. Producers are losing $15 on every barrel at today's prices. When WTI was trading for $100 a barrel, the discount was as high as $45/b.

Barely 10% of Canada's oil lands in the Gulf Coast, the largest refining market in the world and where Canada's heavy grade is preferred over Venezuelan Orinoco and Mexican Mayan crudes. Both Venezuela's and Mexico's state-owned oil companies have refineries on the Gulf Coast, giving them a foothold in the market. By contrast, Canada serves only a dozen refineries scattered across the US. Most of them are outdated and unsuitable for heavy crude.

Cash boost

By some analyst's estimates, Canadian producers would immediately see an extra $5/b premium on the selling price of its crude, a huge source of extra revenue if more crude can find its way to the Gulf Coast.

Yet for all the joy in Calgary, Trump's KXL decision throws the fate of a fourth project oil sands-export project—TransCanada's Energy East pipeline to Saint John, New Brunswick, on the east coast—in doubt and effectively undermines Canada's market-diversification strategy.

Despite being a net oil exporter, Canada imports 0.75m b/d into the Maritime provinces and Quebec, at a cost of more than $1bn a month. A pipeline to the east coast could theoretically ease the import burden, although this would depend on the price of competing grades shipped across the Atlantic. The pipeline could also allow for shipments to Europe and Asia through the Atlantic. For some, this has made the pipeline a higher national priority.

After a rocky start that saw a regulatory panel resign en masse over allegations of conflicts of interest, public hearings into Energy East resumed in January. The delays have pushed the project back until at least 2020.

It probably doesn't matter. It is unlikely that TransCanada will build both pipelines. The company has always had a clear preference for KXL, the more lucrative project, and only turned its attention to Energy East as a backup when it looked like KXL was dead and buried.

For Canada's oil sector, the way to mitigate its Trump risk might be to stick with the drive to find markets

Any pipeline operator knows that the most cost efficient route to market is the shortest distance between two points. Former TransCanada chief executive Hal Kvisle once took out a ruler and drew a straight line on a map from Hardisty, Alberta, the starting point for KXL, to Oklahoma.

Energy East is at a clear disadvantage because the route is longer, traversing two-thirds of the country, and it would compete in a flooded Atlantic basin against imports from West Africa and the Middle East. So, while the politics might favour Energy East, the economics point to the Gulf Coast.

That doesn't mean the path ahead for KXL is easy. After Barack Obama's rejection, Trump's executive order to revive the project has sparked equal parts optimism and consternation complicated by geography, economics and, ultimately, politics on both sides of the border.

KXL became a huge thorn in what is one of the largest bilateral energy-trading relationships in the world. After eight years of intense lobbying, Trump's reversal has been praised by Canadian producers and politicians including the prime minister.

It may yet prove to be a Pyrrhic victory. Trump has also threatened to tear up Nafta and implied some willingness to impose tariffs on imported Canadian barrels—though a summit in Washington between Trudeau and the president in mid-February yielded some conciliatory signals from the White House. Still, it's unclear if KXL is an economic proposition in Trump's realigned market, especially given another idea floated by the new US government, that any construction be done with American steel. Executives in Calgary say this could render the project uneconomic—assuming US steel-makers could even meet the demand. Players north of the border are also troubled by the volatility of the new president's persona. Trump's vow to reduce American reliance on Middle Eastern oil might also open the door for Canadian suppliers—but it also comes alongside the White House's cosiness with Saudi Arabia, which has its own plans to expand in the US. So Canadian producers will be wary of misreading the geopolitics.

For Canada's oil sector, the way to mitigate its Trump risk might be to stick with the drive to find markets. But some of the risk is domestic. Another wildcard for the broader pipeline expansion plans is environmental policy. At the start of the year, the Alberta provincial government introduced a hard cap on oil sands emissions, limiting them to 100 megatonnes a year by 2030. This would allow for continued expansion of about 1m b/d—which is likely to be hit around 2024—without a step change in emissions-reduction technology that would decouple oil sands growth from carbon growth.

That extra 1m b/d is only half of the proposed pipeline-capacity expansions. Suncor Energy, Canada's largest oil sands producer at more than 0.5m b/d, has proposed shutting in higher-cost production to meet those caps, calling into question whether the oil sands will ever need all the new pipeline capacity.

Canadian conventional oil: Market Price Versus Production Cost Margin

After decades of decline, Canada's ageing oilfields have been revived by advances in horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing. Output tripled to around 1.4m barrels a day by 2015, up from 460,000 b/d in 2010, according to the Canadian Energy Research Institute (Ceri)—an industry-funded think tank. According to the National Energy Board (NEB), the country's regulator, that's the highest level of conventional output since 1972.

Horizontal drilling and fracking are helping producers lift recovery rates on many old oilfields that had historically only been able to get about 15% of the original oil in place out of the ground. The Alberta Energy Regulator (AER) estimates that some 1.14bn barrels of conventional reserves remain in the province, against a potential of 20bn more using modern technology. Thus, even a small rise in recovery factors can translate into hundreds of millions of additional barrels at relatively little cost, depending on oil prices.

It's a broad spectrum of risks and rewards. The International Energy Agency (IEA) expects that Canada's oil and gas sector will require $1.1 trillion in new investment over the next 25 years, or some $40bn annually. Around a third of this will be devoted to conventional drilling. Although conventional oil is produced to varying degrees in nearly every province and territory in the country, most of those investment dollars will go to a handful of plays in Alberta and Saskatchewan: the Cardium, the Viking and the Bakken, with a lesser amount to Newfoundland's offshore

The pumping heart of Alberta

At one point in the 1950s, Alberta's Cardium was considered the world's largest oilfield by areal extent, encompassing more than 260,000 square kilometres. Its discovery in 1953 was a fluke—ExxonMobil drilled right through the under-pressured rock without realising it had stumbled on 10bn barrels of oil, barely 1bn of which have been produced to date.

Over the years, it has seen all manner of enhanced development schemes, from water-floods to steam injection. However, it wasn't until 2009 that extended reach horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing pushed the boundaries of the Pembina oilfield into areas previously too tight to drill. Now the prospective area of the Cardium covers 40% of the land mass of the entire province. The keys to success are driven by individual well performance in specific geological sweet spots. The trick is finding them. Fortunately, the resource is well known and the geology is textbook. With the bulk of the exploration work done, getting the oil out of the ground will be more of an engineering feat.

Calgary-based Penn West is one of the Cardium's largest landholders with more than 1m acres in the play. In 2016, it produced 29,000 b/d at a cost of $15.50 per barrel of oil equivalent (boe). At a prevailing WTI oil price of $40 per barrel it was still able to generate C$19.50/b ($14.50/b) in revenue for a net income of C$210m. The company plans to spend C$97m in 2017 to drill 65 wells including 55 water-injection wells and 10 extended reach horizontal producers. According to the company, vertical wells cost just C$0.75m while horizontals are roughly C$3.5m each. Falling costs have been the key driver in the Cardium's resurgence. The Petroleum Services Association of Canada estimates drilling and completion costs will fall 5-8% this year. Casing and cement costs have fallen more than 22% in the winter of 2017 alone. Land prices have also plunged 73% from more than $300 an acre in 2015 to $80 in 2016, making for a compelling economic argument.

Calgary-based Yangarra Resources estimates that a C$3.5m 3,200-metre horizontal well will pay for itself in a little over a year and generate an 80% rate of return, at a WTI price of $40/b, with an operating cost of about C$8/b.

The drawback is that Cardium wells fall off quickly. Good wells post initial production rates of 300 b/d and fall off to less than 50 b/d within six months. Given relatively high drilling costs compared to output, prices are crucial. Cardium activity slipped in 2016 as oil bottomed out below $30, but are expected to return as prices recover. Yangarra, for instance, has identified more than 450 potential Cardium drilling locations on its lands alone, enough to keep drilling for more than 15 years.

Back to the Bakken

Saskatchewan's Bakken is another example of old rock made new with modern drilling. First discovered in the 1950s, it was impossible to produce significant amounts of oil until the arrival of the new technologies. In that time, production has risen more than tenfold, from less than 750 b/d to 75,000 b/d in 2015. Estimates from the Saskatchewan government suggest the formation could hold as much as 0.5 trillion barrels—a number greater than Alberta's oil sands—about 1.5bn of which is considered recoverable with today's technology.

As with the Cardium, much depends on finding productive sweet spots, keeping costs low and maximising initial production rates while stemming steep declines. Unlike the US Bakken, the main Torquay and Three Forks subzones are deeper, which adds to drilling costs. However, those have fallen by more than half in less than two years. Initial production rates are also lower in the Canadian section of the Bakken at around 200 b/d, compared to well over 500 b/d in the US.

A Bakken well that cost C$3.5m in 2014 was drilled for C$1.7m in 2016, according to Crescent Point Energy, the largest operator in the Canadian portion of the play. Crescent Point, which drilled 120 Bakken wells in 2016, has an inventory of more than 1,200 potential locations.

Additionally, declines are steeper than Alberta's Cardium. According to the Saskatchewan Research Council, typical Bakken wells come on around 200 b/d and can fall off to less than 10 b/d after 24 months.

Thus, flattening the decline curve is the key for profitability. A Ceri Study found that a horizontal well in the Saskatchewan Bakken that produces 10 b/d is economic at an oil price of $75, while a well that produces 50 barrels a day is more than profitable at less than $10.

Victory in the Viking

The Viking formation spans much of the prairies in both Alberta and Saskatchewan and is a substantial resource. Of an initial 6.6bn barrels in place, about 5bn barrels were produced prior to horizontal drilling. Unlike other conventional plays, it is relatively shallow at less than 750 metres. And unlike other plays, masses of wells are required to produce significant amounts of oil.

According to Teine Resources, 50% of the reserves sit under wells that are producing less than 10 b/d. Teine, 88% owned by the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, is the largest Viking operator in Canada. In the summer of 2016, it spent C$975m to acquire 21,000 b/d of production from Penn West, or about a third of all production in the play.

Teine has drilled about 1,000 horizontal Viking wells to date and is planning another 300 in 2017, all of them in Saskatchewan. As in other conventional oil plays, those wells are cheap and getting cheaper.

A well that cost C$1.3m three years ago can be drilled for less than C$0.6m. It takes less than 20 days to drill, complete and place wells on production. Even with a lower initial output rate of 50 b/d, the play is profitable at oil prices of $36, according to report by Peters & Company, a Calgary investment bank. This breakeven is comparable to US plays such as the Permian and Oklahoma's Scoop and even the Eagle Ford, although the production levels are lower.

Down to the Duvernay

An emerging area is the Duvernay, which is the source rock for the original Leduc oilfield. Again, the geology is well understood; the trick has been coaxing it out of the ground at a low enough price to make it viable. The advantage is that the Duvernay is widespread and geographically correlated with the Cardium, which makes it an attractive—although much deeper and more expensive—target.

But too few wells—less than 200 to date—have been drilled to accurately gauge whether it's money well spent. At this point, it's a science project. Yet again, the driving factor is well cost. Wells that used to be drilled for more than C$18m now cost less than C$9m, a drop of more than 50% in less than three years, though costs will have to come down further.

Those kinds of numbers are piquing the interest of international majors like Shell and Chevron which are some of the play's top drillers. Murphy Oil is hoping to take its Duvernay production from 3,000 b/d in the fourth quarter of 2016 to 20,000 b/d by 2020. But analysts are split over whether it's a wise move to invest dollars in risky initial stage plays, especially expensive ones. "Although, we expect the Duvernay, specifically, could evolve into an important long-term platform, it is premature to draw such a conclusion".

Going deep offshore

Over the past decade, Newfoundland and Labrador has pumped 20% of Canada's total crude oil per year. However, it's highly variable, dropping to 15% in 2015 from 21% in 2014. Production levels tend to fluctuate not so much on price but rather the pace and timing of new projects and exploration—which is more price sensitive than production itself. With the commissioning of the Hebron project this year, Newfoundland's overall production is expected to climb again to 310,000 b/d in 2019 from 210,000 b/d in 2016, a 50% increase.

Depending on the timing of Statoil's Bay du Nord development the figure could rise higher in subsequent years. Statoil also plans to drill a pair of deepwater exploration wells in the Flemish Pass later this year. Companies typically don't disclose well costs, but an IHS study suggests they wouldn't be economically viable at anything less than $60/b.

Compared to onshore, the offshore has longer lead times and higher upfront capital costs that can't be flipped off with a switch. Economics—while price sensitive—are driven more by the value of the asset itself rather than individual wells. Further, offshore oil is priced on Brent as opposed to WTI, which has given it a higher economic threshold in recent years.

Ceri's analysis of the White Rose, North Amethyst and Hibernia projects show supply costs of $25 WTI while Terra Nova is roughly double at $40/b, but still well within the money at present price levels. But those are existing projects. There won't be a major uptick in offshore exploration or development until prices dramatically improve. Even then, it will take years or even decades to return. Until then, almost all the incremental investment will be onshore.

In Conclusion: "The oil sands get most of the attention and investment, but there is life in the country's oil sector beyond bitumen".

Where is Canada's missing barrels?

This era of lower-for-longer oil prices has raised a thorny question for Canada's oil sands producers: at what point does oil in the ground cease to exist on the balance sheet? The answer is when the US Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) says so.

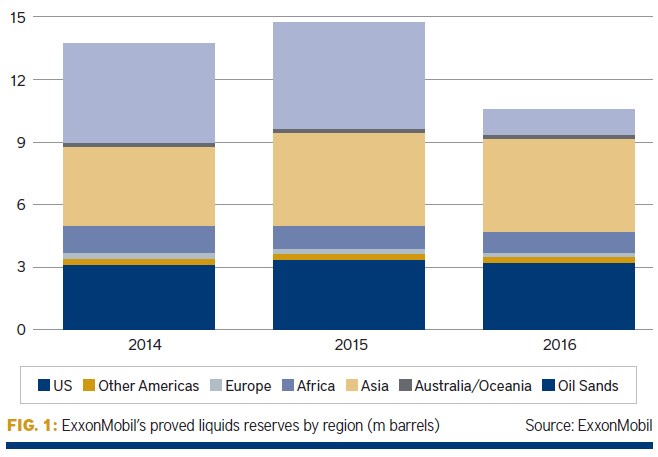

The question became more acute after ExxonMobil was forced to write off 3.5bn barrels of its oil sands reserves in its annual 10-K filing. It amounts to the entire booked reserve base of its Kearl oil sands mine that was commissioned in 2013 at a cost of C$12.9bn ($9.81bn) and another 200m barrels of bitumen at its Cold Lake in situ project. The oil sands writedown slashed ExxonMobil's proved reserves by around 20%.

ConocoPhillips followed suit, cutting its proved oil sands reserves by half, effectively eliminating 1.3bn barrels of oil sands and another 1bn barrels of bitumen resources.

These barrels have disappeared from the accounting ledger without a trace. All told, it amounts to about 3% of Canada's entire proved reserves, which has been touted as the third largest in the world after Saudi Arabia and Venezuela.

The writedowns, however, don't mean that Exxon and ConocoPhilips are packing up and going home. Exxon's Kearl oil sands mine—operated by its Canadian subsidiary Imperial Oil—continues to produce unabated at 170,000 barrels a day. And Exxon insisted in the wake of the writedowns that it is forging ahead, and expects to bring those reserves back onto its books eventually.

The problem is how the SEC requires companies to tally up their reserves. The accounting rules are complex, but essentially say that companies have to use the average price for each month in the previous full year to determine the economic viability of a resource ever being developed. If that price falls below the cost of production, companies must remove the reserves from the books. The price for 2016 after a brutal price crash in the first half of the year was $29.49 a barrel for Western Canadian Select. ExxonMobil reported average production costs for its Canadian synthetic oil projects at $33.64/b for 2016.

This is not an easy decision to make for companies, because it essentially reduces the net asset value of the company. This has been a sticking point with the oil companies for years given that oil sands are capital-cost intensive and so developers would prefer to amortise those costs over the 25-30 years of the asset's producing life.

But rules are rules

Exxon, in particular, was the subject of an SEC probe, in cooperation with the New York Attorney General's office, which asserted that the reserves should have been written off after the oil price plunge in 2015. It signalled in October 2016 that it would have to relent.

Though it speaks to the high cost nature of oil sands development, it's also a bit of an accounting sleight of hand. Global majors like Exxon have invested heavily in oil sands extraction precisely because they have been able to book billions of barrels of reserves and carry them on the books as assets, while knowing it could be decades before they're ever produced. Canada is one of the few places in the world where this is possible.

And Imperial's integrated model has helped shield it from the price downturn. Its upstream segment—which is comprised almost entirely of oil sands output—posted a C$0.66bn loss in the full year 2016. Because it's fully integrated, it buys back those money-losing barrels for its downstream refining segment, which in turn posted a C$2.75bn profit, nearly double the year before.

Likewise, ConocoPhillips is in a 50:50 refining and production joint venture with Cenovus Energy, Canada's largest in situ thermal oil sands producer. The companies plan to increase production to 0.75m b/d and ship it to refineries in Ohio and Texas. What it loses in the upstream it more than makes up for in the downstream.

The bigger question is whether the writedowns affect oil sands development in the longer term. Statoil pulled out of the oil sands altogether in 2016 and Shell has said it doesn't plan to take on any new projects. But on the reserves front, producers have a silver lining. Unlike the SEC, Canadian reserves-reporting rules use projected future cash flows—by definition, forward looking information which isn't allowed in the US—to determine future economic viability. Assuming the recent rise in the oil price lasts until 31 December 2017, almost all of those missing barrels will magically reappear on the books in due course. Even under SEC rules, if oil prices perk back up, the reserves can come back.

For the majors, the oil sands were never only about producing oil, but also about being able to beef up the asset part of the balance sheet. The price crash has shown up the risks of that strategy. The bottom line is that 'all the majors oil companies have carried billions of barrels of oil sands reserves on their books. The price downturn is making them disappear'.

Cenovus Energy goes big in Canada

Canada's Cenovus Energy is primarily known as the country's largest thermal oil sands players, operating some 360,000 barrels per day of steamed, tarry bitumen output in northeastern Alberta.

But with its blockbuster C$17.7bn ($13.19bn) buyout of much of ConocoPhillips' Canadian business, the industry's biggest M&A deal since Shell bought BG, it has suddenly become the country's third-largest unconventional gas producer. In addition to the 50% stake in the Foster Creek Christina Lake (FCCL) oil sands project, Cenovus acquired nearly 3m acres of unconventional shale and tight gas acreage in a region known as the Deep Basin, which straddles the northern Alberta and British Columbia borders.

For Cenovus' shareholders, though, bigger wasn't necessarily better. Shares fell to multi-year lows when the deal was announced in April 2017 over worries about the huge volume of debt the company must take on to finance the purchase. As a result, its gearing ratio jumped from 18% to 40%. But, analysts and insiders say, the Deep Basin was key to the success of the transaction and its long-term value may be being overlooked in the rush to judge the deal.

The Deep Basin has been drilled extensively for years, but advances in hydraulic fracturing technology are transforming the play. It has the potential to become among the most prolific shale plays in North America, rivalling the Marcellus in Pennsylvania and the Permian in Texas.

While a wave of oil sands assets have hit the market, as majors such as Shell, Total, Statoil and Chevron run for the exits, Deep Basin deals of this magnitude don't come around often.

"There was still some growth potential with those (oil sands) assets but it was a non-operated position and we'd already decided to sell some of our Deep Basin gas assets in Canada," according to ConocoPhillips' chief executive Ryan Lance". They had an interest in both the gas assets in the Deep Basin and taking over all 100% of their operated FCCL interest."

ConocoPhillips was producing approximately 120,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day in the Deep Basin—in addition to the 180,000 b/d it shared in the FCCL project at the time of the sale. But it hadn't pumped a lot of capital into the acreage as it shifted focus to more lucrative US shale plays. Low natural gas prices and uncertainty around plans to export liquefied natural gas from the British Columbia coast put the Deep Basin project on the backburner for ConocoPhillips.

Power play

Cenovus Energy took a different view. Its growing oil sands operations consume a vast amount of both gas and natural gas liquids to generate steam and power. The Deep Basin production provided an opportunity to vertically integrate its supply chain and to lower input costs at its thermal bitumen projects, while holding out significant upside (if and when gas prices recover).

Cenovus Energy says it plans to increase output from the acquired Deep Basin fields by around 40%, to 170,000 boe/d by 2019. An analysis by consultancy Wood Mackenzie suggests that with a more ambitious drilling programme it could nearly quadruple output on those lands to 350,000 boe/d by 2021, though it would need higher gas prices and reduced drilling costs to pull that off.

Cenovus Energy will target a virtually untapped formation called the Spirit River that underlies most of the ConocoPhillips lands. Wood Mackenzie estimates that the Spirit River formations could hold 700m boe, and the company says it has lined up around 700 drilling targets already.

If Cenovus can indeed quadruple output from its Deep Basin gas acreage, it will be in a strong position to supply new LNG export plants, if they're built. It's a speculative bet, but a compelling one.

It also represents a significant reversal in thinking for the Canadian stalwart. Cenovus was spun out of Encana in 2009, when investment bank analysts were pressing large complex oil and gas companies to simplify, precisely to become a pure play oil sands producer. Encana took more than 90% of the company's gas in the split to become a pure-play gas producer.

Both are now rediscovering the virtues of diversification. Encana has abandoned its once blinkered gas focus by taking significant positions in US Permian light oil. And through this deal, Cenovus is reducing its exposure to the battered Western Canada Select oil price benchmark with a big bet on British Columbia gas.

The fundamental question is that, can the Deep Basin help Cenovus Energy make a success of its ConocoPhillips deal?