Energy Security Intelligence Research

ESIR

ESG STRATEGY RISK and COMPLIANCE PLANNING AGENDA 2050

NIGERIA

The Nigeria oil and gas sector is made up of the upstream sector: comprising exploration, drilling and production of crude oil including the premium bonny light crude, a midstream sector comprising transportation, and refining of crude oil, as well as a downstream sector comprising of the importation, storage and distribution of petroleum products such as premium motor spirit (PMS), automotive gas oil and dual purpose kerosene-an aspect still highly regulated by the Federal Government of Nigeria. The 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria vests all petroleum in situ in the federal Government of Nigeria.

The 1999 constitution which is the fundamental law of the Federal Republic of Nigeria vests in the federal Government of Nigeria title over all petroleum, which includes natural gas, under, or upon, any land in Nigeria, its territorial waters and its exclusive economic zone. The primary piece of legislation regulating the exploration, production and distribution of petroleum in Nigeria is the Petroleum Act cap. P10 laws of the federation 2004 (the PA). The Petroleum Act (as specified earlier), vests in the Federal Government, the ownership of petroleum resources in Nigeria.

Under the Act, all activities ranging from exploration to production and distribution of crude oil and Petroleum Resources in the issue of licences and permits. The Act gives the Minister power to issue regulations, necessary for the discharge of his/her duties under the Act. The Petroleum Drilling and Production Regulations is a subsidiary legislation made pursuant to the Petroleum Act and it regulates thoroughly natural gas, exploration and production activities.

Regarding taxes, rents and royalties, the relevant legislation and subsidiary legislation are the Petroleum Profits Tax Act, the Companies Income Tax Act and the Petroleum Drilling and Production Regulations. The first two regulate the taxation of profits made from the production and distribution of crude oil and natural gas respectively, whilst the last specifies the rates for royalties and rents. The National Environmental Standard and regulations Enforcement Agency Act (NESREA) to a limited extent, the Environmental Impact Assessment Act (EIA) and the Environmental Guidelines and Standards for the Petroleum Industry in Nigeria (EGASPIN) prescribe environmental and emission standard applicable to activities related to crude oil and natural gas operation in Nigeria.

Under the auspices of the Nigeria Gas Meter Plan, the National Domestic Gas Supply and Pricing and National Domestic Gas Supply and Pricing, the Federal Government of Nigeria, introduced a year-to-year graduated pricing regime for gas sale in the domestic market, in order to encourage people to invest in the natural gas subsector. It is expected that by the year 2014, the Government would no longer intervene in the domestic gas market as the market would have become mature enough and competitive. The Department of Petroleum Resources (DPR) regulates gas activities in Nigeria. The Gas Aggregation Company of Nigeria is expected to ensure the availability of gas supply to the domestic market.

NIGERIA OIL CAPITAL: PORT-HARCOURT CITY

Breaking News on Instability in the Niger Delta of Nigeria!

Nigeria files US$635m claim against Total and AGIP

Sectors: oil and gas

Key Risks: profit warnings, contract frustration, militant attacks, civil unrest

Nigeria’s government filed a claim of US$635m against Total and AGIP for 57m barrels of undeclared crude oil shipped out of the country between 2011 and 2014. The claim followed the discovery of discrepancies between Nigerian export records and import records from ports of entry in the US used by Agip and Total. The hearing is expected to begin next week at the Federal High Court in Lagos. The Nigerian Government is claiming US$490.5m from Total and US$146m from AGIP. There are indications that prosecutors will be filing claims against other multinationals, such as Chevron and Exxon-Mobil. The likelihood of associated contract frustration is low, but cannot be ruled out. Civil unrest and militant attacks in the Niger Delta may increase as a result of the news.

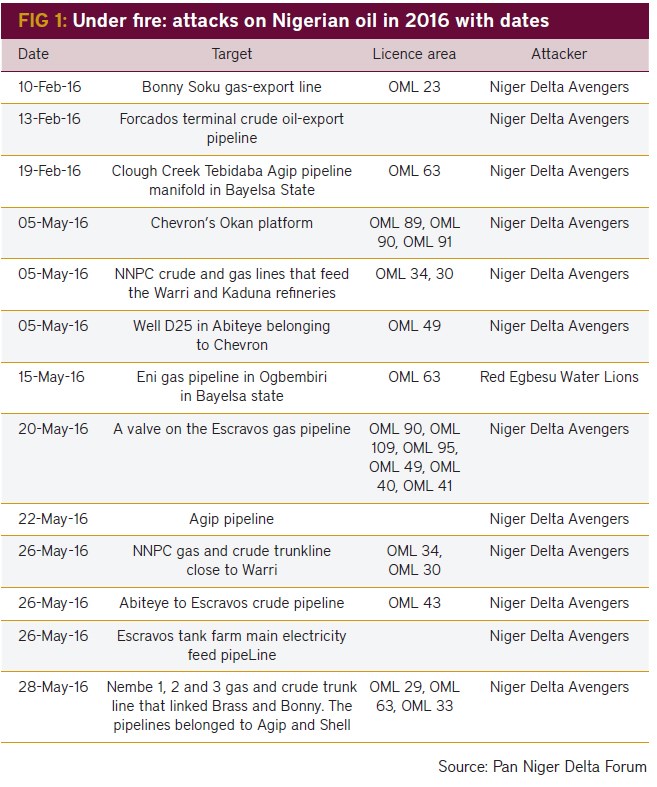

However, in the oil, gas and transportation sector, the key risks is political violence and trade disruption. Although, representatives from the Nigerian militant group, Niger Delta Avengers (NDA), reported that they were ready for a ceasefire and a dialogue with the government. The NDA have conducted a wave of attacks on oil facilities across the region over 2016, driving oil output to record lows. The group wish to see more oil revenue trickle down to the Niger Delta, as poverty and unemployment levels remain high. However, any ceasefire is expected to be difficult to enforce owing to the factionalised nature of militants operating in the region, and the loose control of militant chiefs over youths. Sporadic attacks cannot be ruled out during talks over a ceasefire agreement.

Moreover, the IMF revised down its 2016 growth forecast for Nigeria. The economy is now expected to contract by 1.8 per cent in 2016, for the first time in over 20 years, a significant downgrade from April's 2.3 per cent estimate. The Nigerian economy has been affected by foreign exchange shortages as a result of low oil prices and militant attacks constraining oil exports, low power generation, and weak investor confidence. Following the removal of the currency peg in June, the naira weakened against the dollar by almost 30 per cent, and inflation in Nigeria reached 16.5 per cent in June. Liquidity remains thin, although this is expected to ease over the coming year.

Nigeria seeking investment ‘to develop gas-based industries hub’

Nigeria needs more than $35 billion in investments to position the country “as a regional hub for gas-based industries”, the head of the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) has said.04 Nov 2016 Energy and infrastructure finance Projects Major projects Energy Infrastructure Africa Western Africa

NNPC group managing director Maikanti Baru told the Nigerian Gas Association’s 10th international conference and exhibition in Abuja that around $35.4bn is needed to fund activities including gas exploration and production, power plant projects and flare gas commercialisation.Baru also said investment opportunities worth an estimated $51bn exist in Nigeria’s midstream and downstream gas sector.A further $16bn worth of investment will be needed to support infrastructure projects for the gas sector including central gas processing facilities, liquefied petroleum gas plants and gas transmission services, Baru said.“Beyond growing gas for the power sector, there has been a strategic positioning of the sector to support massive gas based industrialisation,” Baru said. “The intent is to position Nigeria as a regional hub for gas-based industries such as fertilisers, methanol, petrochemicals and central processing facilities.”Baru said a “first effort” towards the ambitious plans for the gas sector is a planned 30 square kilometre gas-based industrial park at Ogidigben, in Delta State, known as the Gas Revolution Industry Park (Grid). Baru said the facility “will be Africa’s largest purpose built gas park supporting gas based industries”.The NNPC unveiled plans for the Grid in May 2013, however the project has been beset by delays and a ground-breaking ceremony for the project did not take place until last March.Former Nigerian president Goodluck Jonathan said at the ceremony: “It is my intention to make the gas park most investor-friendly. It will be an export processing zone to attract the global market. This project will meet world standard.”Jonathan said the Grid will “be Africa’s largest gas and fertiliser export processing zone when completed and generate thousands of jobs for citizens”. Jonathan said around 3,000 jobs would be created during the construction phase. He also announced the setting up of a special steering committee to oversee the project and report on progress to the Federal Executive Council on a weekly basis.According to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), Nigeria was the world's fourth-largest exporter of liquefied natural gas in 2015. The EIA said Nigeria’s natural gas sector “is restricted by the lack of infrastructure to commercialise natural gas that is currently flared”.A report released last year from consultancy Ernst & Young (80-page / 2.4MB PDF) said Nigeria had been the largest recipient of foreign direct investment (FDI) in Africa over the last decade, 80% of which had been invested in the oil and gas sector.A separate report, ‘Landscape for Impact Investing in West Africa’ (56-page / 1.62 MB PDF), said West Africa is becoming an increasingly attractive regional market for “dynamic impact investing’’ on the continent. The report said West Africa still accounts for “a significant share of sub-Saharan Africa’s (SSA’s) FDI, attracting an average of 35% of FDI inflow in SSA between 2004 and 2013”.Nigeria attracted around half of the region’s FDI inflow and “is currently the third largest recipient of FDI in SSA”, behind South Africa and Mauritius, the report said.Towards the end of last year, Chinese steel pipe manufacturer Jiangsu Yulong Group broke ground for a major manufacturing plant in Nigeria's Lagos Lekki free trade zone, aimed at supplying the country’s developing oil and gas industries.

Troubles in the Niger Delta continue

Sectors: oil and gas

Key Risks: fines and settlements; civil unrest; pipeline vandalism

The UK’s High Court will determine whether Royal Dutch Shell will face trial in the UK over oil spillages in Nigeria's Niger Delta. Delta communities, claiming domestic courts are unfit to try the case, are suing the company for pollution in the restive region. The claim follows a US$84m agreement Shell made with another community in 2015 after two pipeline leaks. Meanwhile, the militant group Niger Delta Avengers (NDA) stated they are prepared to resume attacks, declaring that no progress had been made during talks with the government. This also follows a statement issued by the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) that they had lost confidence in President Buhari. Attacks on oil and gas infrastructure will likely increase over the coming weeks. Both issues highlight the fragile and volatile security situation in the oil-rich region.

ONES TO WATCH

Political Instability in Nigeria: Buhari returns to Nigeria after extended medical leave

Sectors: all

Key Risks: political uncertainty; policy hiatus; succession threats; sectarian tension

On 10 March 2017 President Muhammadu Buhari returned to Nigeria following extended medical leave in the UK. Public discussions have been pervaded by the president’s health, with Nigerians drawing parallels with former president Musa Yar’adua who died in office in 2010. However, in Buhari’s absence Vice President Yemi Osinbajo has re-energised politics, pressing ahead with much needed reforms. Nigeria announced an economic recovery plan on 7 March 2017, incorporating various measures to bolster economic growth, which is projected to expand by 2.19 per cent this year. A US$500m Eurobond issuance is also expected shortly, in addition to a US$1bln World Bank loan to plug a record budget deficit. However, concerns over Buhari’s health will likely persist, increasing political uncertainty. The prospect of Osinbajo serving the remaining two years of Buhari’s term raises the risk of heightened sectarian tension given Nigeria’s federal system. It also raises concerns over a slowdown of the reform agenda, which may prove fatal to the ruling APC as the 2019 elections loom.

Nigeria looking up: But political instability, security and economic risks still remain

Over the next five years, the federal government of Nigeria is looking to attract about $10bn in new investment into the country's energy sector. About $6bn is needed to fix its refineries and reduce petroleum product imports. The Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) also intends to upgrade total refinery processing capacity to 0.7m barrels a day; a level that, even at 50% utilisation, would meet domestic demand. (Current nameplate capacity is about 450,000 b/d, but actual processing is much lower.) Much new spending is needed for gas pipelines and processing capacity; the NNPC has its own plans to build a 0.5bn cubic-feet-a-day gas processing plant to feed the power sector. Nigeria has over 10 gigawatts of installed capacity for gas-fired power supply but is barely able to get its electricity power supply above 4GW due to insufficient gas feedstock.

Beyond the NNPC, the government also hopes to boost investments in oil and gas exploration. A marginal-field licensing round is scheduled for the third and fourth quarter of this year, while a proper block licensing round could be held by the end of 2017 or early 2018. It would be Nigeria's first licensing round in about 10 years.

The plans are therefore great. Yet, for all its oil and gas potential, investment in recent years has been weak. Offshore exploration activity has slowed considerably while major field development projects earlier earmarked for 2017-18 have been pushed further back to 2019-20. While major new projects are being brought on stream in neighbouring countries such as Ghana, Côte d'Ivoire, Congo and Angola with several others lined up for first oil or first gas before the end of 2017, Nigeria has only the Egina field in Q1 2018 as the major project to look forward to.

The main reason for the slow progress in Nigeria has been the lack of passage of the Petroleum Industry Bill, an effort to harmonise all laws regulating the Nigerian oil and gas industry into one single document. The bill has been in and around the legislative arm of government since 2007, when it was first submitted to the Senate. Due to the perceived haircut to the value of projects implied by the bill's terms, many were suspended and some postponed—especially in the deep water, where major changes to fiscal terms were expected.

The peace is likely to be sustained as long as the government continues to engage the Niger Delta region constructively.

The government has now taken several steps to address this delay in passage. First, the bill has been split into four parts, a governance bill, a fiscal-regime bill, a downstream and midstream bill and a petroleum revenue management bill. The first section, called the Petroleum Industry Governance Bill (PIGB), has just been recently passed by the Senate for the consideration of the lower house, the Federal House of Representatives. Following passage by the representatives, the bill will be reviewed by a sitting of both houses and then passed into law with the assent of the president.

The passage of the first section, that is, the governance bill, is expected to clear the way for deliberations to begin on the subsequent drafts, especially the fiscal bill, which is viewed as the most important section. This is because it is expected to clear the air on how the deep-water assets will be taxed, what the government plans to do with gas under the production-sharing contracts (PSCs) and how it intends to review the general taxation of the petroleum industry to generate more revenue. Furthermore, the petroleum host community fund, a 10% levy on profits before tax, which will be used as a community-engagement scheme, is likely to be included in the fiscal bill. The draft copy of the National Petroleum Fiscal Policy released in February 2017, which will form the basis for the fiscal bill, already indicates a favourable reduction in taxes, which operators are likely to find attractive. Gas operations, which previously had no fiscal terms under the PSCs, are to be taxed lower than oil. However, focus on the fiscal policy will have to wait for the full passage of the governance bill first into law.

Regulatory revolution

The governance bill intends to revolutionise the way the state relates with the oil and gas industry. A new regulator, the National Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NPRC) will be created, combining the functions of the current upstream regulator—the Department of Petroleum Resources (DPR)—the Petroleum Inspectorate and the downstream regulator (the Petroleum Products Pricing & Regulatory Agency). The benefits of having a single industry regulator to provide all necessary licences and permits cannot be over-emphasised. The current regulatory framework has proven to be mostly weak and inefficient with operators having to respond to several regulators to get various licenses or permits.

The bill will also streamline the powers of the petroleum minister to award or renew oil blocks, making them reflect the will of the NPRC as against using his own discretion. NNPC will be restructured into a new national oil company that will be fully commercial with no regulatory functions or powers. The equity will be held by the federal government (50%) and Bureau for Public Entreprise (BPE, 50%). The BPE will sell down 40% to the public within five years. This is likely to be a challenging task as the NNPC is currently a behemoth of an organisation, with over 30 subsidiaries. All these subsidiaries are expected to be re-absorbed back into the new organisation before it is then transformed into a commercially focused oil company. The Nigerian Gas Company is also likely to be listed on the stock exchange.

In short, the bill seeks to improve transparency and accountability in the oil and gas industry. However, implementation has always been the problem. So while the bill could be passed into law, anticipate the actualisation of these plans to be drawn out further than expected in the document.

Another key concern for investors in Nigeria has been security. Most of these worries were based on the attacks in 2016, which showed the extent to which the militants could really damage oil and gas investments. They succeeded in shutting down key oil export terminals such as Brass River, Bonny Light, Escravos and Forcados for extended periods. Forcados stayed offline for nearly nine months only to be attacked and shut down for a further seven months.

But, so far in 2017, the Niger Delta has been peaceful—the result of extensive negotiations between the government, the militants and Niger Delta communities. The communities provided the government with a list of 16 demands largely focused on getting more share of the revenues from the oil and more ownership of the reserves. Although I doubt that the government will be able to meet most of these demands, the communities seem to appreciate the more engaging framework of the current talks they are having with the government.

The visits by the acting president Yemi Osibanjo to the Niger Delta over several months from January to March are a sign of the government's good intentions to tackle the issues of the region. Furthermore, the government also restarted the amnesty payments to ex-militants and increased the budgetary provision for the payments from 20bn naira ($6.3bn) annually to over 65bn naira to cater for previous payments missed and also cover additional payments, likely to the new militant groups that came on the scene in 2016. These steps, in addition to other forms of less-publicised engagements with the militants via the Pan Niger Delta Forum have helped to restore stability to production; allowing repairs and lifting of force majeures on major oil exports, especially Forcados.

However, a sense of fragility persists over the recent peace in the region; the insecurity has not totally abated due to continued kidnappings and smaller attacks on gas pipelines by some groups. Illegal refinery operators continue to break into pipelines to steal crude oil to feed their plants. The government had initially mulled the idea of converting these operators into a form of cottage refineries but has since suspended the idea due to the risk of further degradation of the environment. Vandalism of petroleum product pipelines remain high, with the NNPC reporting more breaks in March than in previous months. These breaks continue to hinder the functioning of NNPC depots around the country, which would ease the distribution of petroleum products and help the NNPC reduce its distribution expenses. Furthermore, the delay in start-up of the oil spill clean-up program in the Niger Delta, despite its elaborate kick-off over a year ago, could prove to be a distraction from the ongoing engagements. The delay is largely due to lack of funding from the government and its partners, the international oil companies. Continued postponement could create doubts about the sincerity of the government in really tackling the key issues of the region. Still, the peace is likely to be sustained as long as the government continues to engage the region constructively. The improvement in government revenues from oil due to the return of the Forcados pipeline and passage of the budget could ensure release of funds for payment to ex-militants and also investment in capital projects and infrastructure in the region.

Succession woes

The third factor in the country's lack of investment remains the political angle. This is largely two-fold. The first is a potential succession problem due to the persistent health concerns of President Buhari. The second is the tense relationship between the executive and legislative arms of government. Buhari has had to make two trips to the UK to get medical attention on an undisclosed illness and also had to reduce his involvement in the running of the country. Although, power was delegated to the vice president as expected by the constitution, worries about Buhari's inability to continue in office beyond 2019 raise questions about the impact of a change in personnel at the top of the country. Investors may take comfort in the competence shown so far by vice president Yemi Osinbajo. At least until 2019, when the elections are due, key decisions will be made in a timely fashion. This is largely reflected in the Enabling Business Environment 60-day plan launched in February, which has helped reduce some of the problems of doing business in Nigeria. From entry and exit into the country to accessing credit, registering a company, obtaining permits and facilitating trade across borders, the government has shortened previously long timelines.

[65bn naira - Amount Nigeria's government is spending on amnesty payments in the Delta]

But the relationship between the executive and the legislative continues to be a sour spot. The 2017 budget was finally passed in June after several months of delay by the National Assembly (a combination of the upper and lower houses of the legislature). The Federal House of Representatives announced suspension of deliberations on the governance bill passed by the Senate pending conclusion on discussions about a $17bn disparity in the country's oil revenues when figures from all the various government agencies are compared. According to the House, the figures from the NNPC, DPR, Nigerian Navy, Nigerian Maritime Administration and Safety Agency indicated a discrepancy of over 48m barrels during the years 2011 to 2013; a period during which oil was sold at over $100 a barrel. While this is a necessary investigation, this discussion could further delay passage of the PIGB.

Recently the House also passed an amendment to the NLNG Act (for liquefied natural gas) to include some new duties and charges not initially included in it. This amendment, which reduces the profit share of partners in the NLNG while increasing the government share of benefits (taxes) could put current discussions with partners over a new LNG train 7 at risk. The Senate has also had its own fair share of disagreements with executives, most recently stopping the concessioning of the Port Harcourt refinery to Italian oil major Eni and local oil company Oando, after a protracted discussion between the petroleum ministry and these companies.

Despite all these obstacles, the open and entrepreneurial focus of the current leadership of the petroleum industry and the strong support from both the president and vice president (acting president) provide some basis for optimism on the fortunes of the industry. The ability of the current junior minister for petroleum, Emmanuel Ibe Kachikwu, to engage constructively with various stakeholders has also ensured that industrial actions and other industry constraints are less of an issue than they've been in previous years. This was critical to getting a deal with the international oil firms that enabled Nigeria's exit from its joint-venture cash call obligations. The exit lets Nigeria spur new investments by the joint-venture partners as they seek to get their debt payments from Nigeria through incremental production, and is expected to see the country produce more crude oil from 2018. Involving the legislature in the discussions that led to the creation of the Petroleum Sector Roadmap launched in 2016 has also helped to create a good working relationship with the upper and lower houses.

Overall, the combination of the steps taken by the government to de-risk operations in the Niger Delta, pass key legislation and create a more collaborative environment in the oil sector are major positives that should attract new investment into the country. Although security and political risks remain, Nigeria is increasingly open to investment especially in its crucial oil and gas sector.

However, long-awaited legislative progress, peace in the Delta and some astute political management are creating optimism in the country's energy sector.

Court dismisses Nigerian claim against UK parent company

The Court of Appeal has dismissed a claim brought by two Nigerian community groups against Royal Dutch Shell (RDS) for environmental damage caused by one of its subsidiaries.

The groups were unable to show that RDS rather than the subsidiary, the Shell Petroleum Development Co. of Nigeria Ltd (SPDC), owed them any duty of care. The group's only remedy was to sue SPDC in the Nigerian courts, as the English court had no jurisdiction over SPDC.

The case was, however, a "finely balanced" one, which included a "vigorous" dissenting judgment from appeal court judge Lord Justice Sales, according to energy litigation expert Richard Dickman of Pinsent Masons, the law firm behind Out-Law.com.

"In this case, the argument for a duty of care rested on the degree of control exercised by RDS over its Nigerian subsidiary, and the degree to which its health and safety and other policies were imposed on the subsidiary," he said. "Clearly, the more financial and operational control, and the more policy influence, exerted by the parent over the subsidiary, the greater the risk of such a duty of care being found to exist."

"The main obstacle to bringing these sorts of claims is the fundamental principle that companies have separate legal personality. Courts are generally unwilling to 'pierce the corporate veil' unless the corporate structure is a deliberate device to conceal wrongdoing. To overcome this obstacle, the claimants had to show that the parent company owed a duty of care to the subsidiary's employees or the local community. The court then faced the difficult task of determining whether it was at least reasonably arguable that such a duty of care existed, and therefore whether the court has, or should exercise, jurisdiction over the claim," he said.

Dickman said that the courts had agreed to accept jurisdiction in a number of these cases in the past. For example, in the 2000 Lubbe v Cape Plc case, the House of Lords found in favour of the South African claimants, for whom it would be difficult to pursue their claims in South Africa. However, the courts have only found in favour of the employees of a subsidiary, but not the community affected by the subsidiary's activities, on one occasion, in the 2012 Chandler v Cape Plc case, where the parent company had employed a doctor whose specific role was to protect the employees of the subsidiary.

Multi-national parent companies face claims in England arising out of the activities of their foreign subsidiaries on a fairly regular basis, Dickman said. Suing the parent company can be attractive where the parent company has "a deeper pocket" than the subsidiary, or where it can act as an 'anchor defendant' to ensure that the English courts have jurisdiction to hear the claim, according to Dickman.

The community groups were seeking damages for what they claimed was "serious, and ongoing" pollution and environmental damage caused by oil leaks from pipelines and associated infrastructure in and around the Niger Delta. SPDC operated the pipelines and associated infrastructure as part of a joint venture agreement between itself, the Nigeria National Petroleum Corporation, Total Exploration and Production Nigeria Ltd and Nigeria Agip Oil Company.

The groups had argued that RDS' "knowledge of and control over SPDC's operations and their foreseeable effect on the environment and communities" created a "relationship of proximity" between the parties. SPDC, however, provided evidence that it was responsible for "all operational decisions" in Nigeria; that it, rather than RDS, had the "specialist knowledge and experience" to operate in the country and that it was SPDC, rather than RDS, that held the necessary licence from the Nigerian authorities.

The court found that RDS operated a "centralised system based on industry standards and the Shell Group's own developed best practice". However, this did not point to a "sufficient degree of control of SPDC's operations in Nigeria by RDS to establish the necessary degree of proximity". The idea behind the system was "to ensure that there were proper controls and not to exercise control", the judge said.

"There were reputational concerns (in part in relation to personnel), there was concern about losses of oil and environmental damage, there was a desire to ensure that proper systems were put in place to reduce such losses and environmental damage; and there was the establishment of an overall system which was there to ensure best uniform practices," the court said. "However, the claimants have not demonstrated an arguable case that RDC controlled SPDC's operations, or that it had direct responsibility for practices or failures which are the subject of the claim."

Lord Justice Sales disagreed, finding that the groups had a "good arguable case … that RDS did involve itself in the management of the operation and security of the pipeline and facilities in such a direct and substantial way, exercising a degree of real control in relation to those matters going significantly beyond the mere setting of group-wide standards by the Shell Group's central management teams".